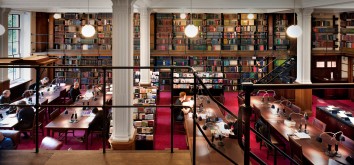

Amanda Stebbings, The London Library

A haven for the insatiably curious, or a treasure-trove of knowledge, the London Library has always been at the heart of cultural and literary life since it was founded by the writer and thinker Thomas Carlyle in 1841. It is difficult not to wander through the bookstacks wondering how many scholarly revelations have been made or fiendish fictional murders plotted within these walls. Today, we count many distinguished writers and journalists as members and the role that the Library’s collections and ever-helpful staff has played in their work can be seen in the frequent acknowledgements we receive:

“The London Library is my favourite place in the whole of London. A unique resource and a wonderful place in which to read and research.” (John O’Farrell)

As an institution the London Library is unique and members each have their own experience of it. For some, it is a calm place to work. Following an extensive refurbishment programme the Library has five designated reading rooms and a range of individual writing spaces fitted into nooks and crannies throughout the building. An informal community of writers has developed at the Library and they relish the opportunity to work amongst their peers.

“Amid the cram of London, this building has been a refuge and a tonic. The Library has also been, on a much more practical level, my office. Granted it’s a communal office, but I work better there than anywhere else. I can’t quite describe the peculiar little skip of joy inside me when I enter the Library’s front door, but I get it every time.” (Nikki Gemmell)

Whilst the main Reading Room is a silent reading area where electronic equipment is not permitted, the use of technology is encouraged throughout the rest of the Library, with wi-fi coverage and free access to a very wide range of electronic resources including JSTOR and the recently added 17th-18th Century Burney Collection of Newspapers. The e-library is one of the most rapidly expanding collections, available for members both in the Library and remotely via our website (www.londonlibrary.co.uk).

“I use the Library as a secondary, and occasionally a primary, source for research, and I also love to write there, its atmosphere being perfect for work. It is the only library I know which grants every reader open access to the book shelves, and this is invaluable if you are writing and suddenly need to research something unexpected. It has made the process of writing more enjoyable and less solitary, as I have made new friends there and there is always an opportunity to discuss one’s work with other writers, or just have a good gossip.” (Christopher Simon Sykes)

For other members, it is the depth and breadth of our collections that is the draw. We hold over one million items, 97% on open access and almost all available for loan. Here you can find recently published volumes shelved next to books from the 1730s. Our periodical holdings cover 750 current titles as well as backruns of over 2,000 titles, many of which are now discontinued. The focus of the collection is arts and humanities, and we are especially strong in history, topography, philosophy, biography and religion. There are over fifty languages represented on our shelves, with particular strengths in French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish literatures.

The Library’s unique classification scheme was created around the collection by Librarian Charles Hagberg Wright (1893-1940, our longest serving Librarian to date). Having despatched the arts and humanities books to their appropriate areas he was left with some 40,000 volumes which formed the wonderfully named Science & Miscellaneous section, and one fortuitous result of this scheme is the element of serendipity that it introduces. There are not many libraries where books on Butterflies sit next to Camels, or Dentistry to Devils, or even Housing next to Human Sacrifice. It is this juxtaposition that can lead writers in different and unexpected directions, creating connections that they had not considered.

One of the Library’s greatest resources is its staff, and our specialist team are not afraid to tackle the tricky enquiry. Recent enquiries have covered the peasant costume of medieval Spain, historical uniforms of the Hungarian army, and the various patterns to be found on larks’ eggs. It is a service that is greatly appreciated by the members who visit the Library and by those who use our postal service.

“I was researching Vichy France for Charlotte Grey. The only reliable history was by the American historian Robert Paxton…He said that two out-of-print French novels of the late forties had some flavour of the period, but that was all. I was living in France at the time. I faxed the London Library more in hope than in expectation. Both novels arrived by post within the week.” (Sebastian Faulks)

Membership of the Library is open to all, and at less than £40 per month is cheaper than most gym fees. Here you can exercise your mind and then your body, if you wish, walking the eight floors up to the Members’ Room from the Basement. The Library has introduced a number of initiatives to ease the financial burden, such as reduced fees for young people and the spouses of members, and supported membership through the London Library Trust for those to whom the membership fee would be a barrier to use.

And as for the fiendish fictional murders, maybe someone has beaten me to it…

“How is the Library different from others? Open stacks…but ours are more magical, sinister and beguiling than anyone else’s. I always thought that ‘Murder in the London Library’ would be a promising book – with victims being squished in the rolling shelves of Periodicals, and electrocuted pulling the light cords in Biography, trapped for weeks in Religion or German Literature before anyone noticed – it has great potential.” (Artemis Cooper)