Vipin Chauhan[1]and Gillian Ragsdell[2]

Introduction

In the Autumn 2018 edition of K & IM Refer, there was a discussion and an analysis[3]about the development of a holistic approach to knowledge management in a not-for-profit partnership project, Charnwood Connect. The article described how both technical and social aspects were integrated into the project’s knowledge management strategy, enabling partner organisations to work together, learn from each other and collectively improve local advice, information and support services. In this follow-up article, we offer a more theoretical reflection on the role of knowledge brokers and knowledge brokering processes based on the experiences of the first author as Charnwood Connect’s Knowledge Management Officer. Definitions vary but for the purposes of this article, knowledge brokers fall into two distinct but complementary practitioner categories. The first category refers to knowledge practitioners who have an explicit or niche responsibility for knowledge brokering and sharing such as Charnwood Connect’s Knowledge Management Officer. The second category refers to practitioners such as line managers who have a more implicit or an incidental responsibility for knowledge brokering.

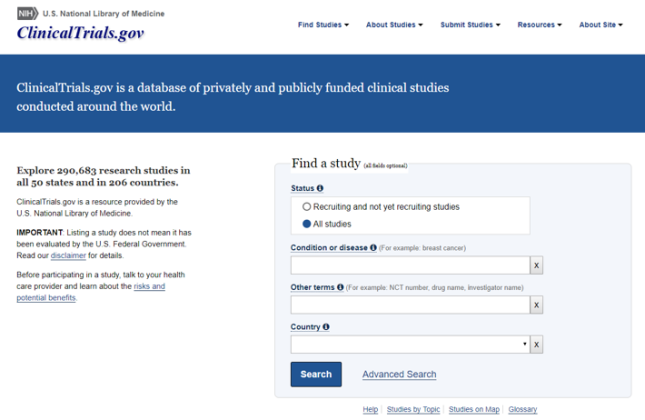

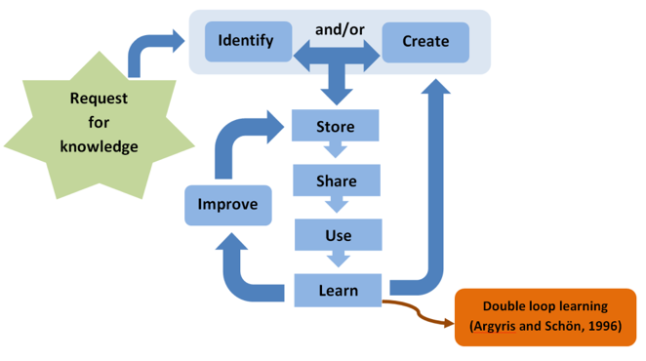

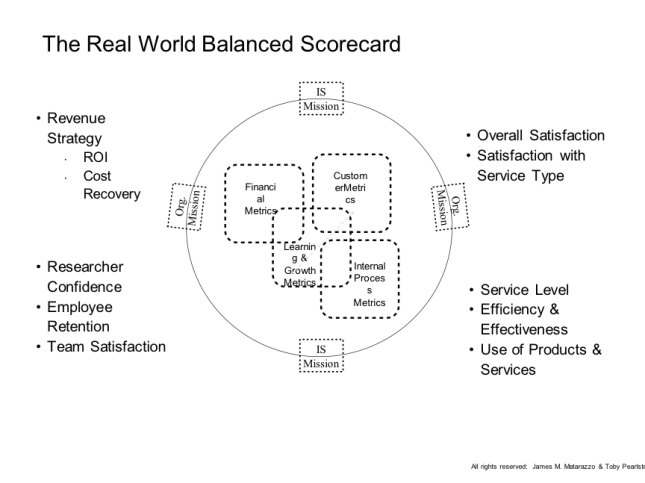

Organisational knowledge management strategies comprise a series of sequential processes, amongst which knowledge sharing is one (Figure 1). One of Charnwood Connect’s primary objectives was to strengthen knowledge sharing by partner organisations in order to improve local services. The deployment of a niche Knowledge Management Officer, the development of the Knowledge Hub, the establishment of a face-to-face practitioners’ forum as well as other joint initiatives were all part of Charnwood Connect’s strategy to increase the frequency and depth of knowledge sharing amongst practitioners. As knowledge sharing and joined up working were so fundamental to Charnwood Connect’s mission, this article focuses on these aspects, especially the contribution of knowledge brokers and knowledge brokering processes.

Figure 1: The Knowledge Management Cycle (Evans, Dalkir and Bidian, 2014)

Knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing is fundamental to human evolution and the transmission of ideas, innovations, values, beliefs and cultural practices. The advent of information technology, the knowledge economy, more knowledge-intensive work and the proliferation of social media have intertwined lifestyles and communities globally. In organisations, knowledge sharing is vital as “….the process of spreading knowledge is believed to stimulate innovation” (Ward, House and Hamer, 2009, p. 269). Without effective knowledge sharing the knowledge management chain of “….knowledge acquisition, storage, dissemination, and application” (Teng and Song, 2011, pp. 104-105) is weakened.

The process of knowledge sharing assumes that there is willingness amongst two or more individuals or organisations to exchange knowledge, with one wanting the knowledge possessed by the other. This presumptive and implicit social contract to share knowledge between two or more stakeholders underpins the success of knowledge management processes in organisations. Thus, knowledge sharing is a mutual process involving human interaction, negotiation and reciprocity and through “….an act of reconstruction” (Hendriks, 1999, p. 92), knowledge is transformed and “common knowledge” (Dixon, 2000, p. 13) is co-created.

Issues and challenges

As discussed above, knowledge sharing involves human interaction, social relationships, personalities and politics, and is not just about knowledge access and exchanges through impersonalised exchanges or technological mediums. Just to track back momentarily, the origins of knowledge management are rooted in the efforts of practitioners who were tackling knowledge management challenges before academics and researchers took interest (Wiig 1997; Dalkir, 2005; Serenko et al,2010). Indeed, “….many of the initial academic papers were case studies and re-conceptualisations of what had already occurred in practice” (Serenko et al, 2010, p. 16). The practice roots of knowledge management are important to acknowledge as they serve to validate practitioners’ experiences of knowledge sharing and reinstate their stake in knowledge sharing processes. Perhaps a fuller acknowledgement of this can even entice practitioners to reclaim knowledge management as a form of professional practice, not just a subject for study by external researchers.

Dislocating knowledge sharing from its practical application can contribute to “know-do” gaps (Greenhalgh and Wieringa, 2011, p. 503), for it is practice that gives a real world meaning to practitioners’ actions and behaviours (Cox, 2012) and forms the “materiality of social relations” (Gherardi and Nicolini, 2002, p. 421) in work organisations. Workplaces and professional networks are manifestations of social relationships (Wenger, 1998; Cox, 2012; Schatzki, 2012); and when organisations develop knowledge sharing strategies, it is vital to appreciate the power and potential of human agency. Human agency in the form of niche knowledge brokers and other practitioners with incidental responsibilities for knowledge sharing can transform knowledge management principles into practice and help build an organisation’s capacity to do more.

Knowledge brokers

Knowledge brokers are defined in different ways and can include individuals, organisations and even whole countries. The focus of this article is on human agency in knowledge brokering processes and the role of knowledge brokers such as Charnwood Connect’s Knowledge Management Officer. Knowledge brokers can be described as practitioners who are catalysts for reducing the “knowledge distance” (Markus, 2001, p. 88) between knowledge producers and (re)users, and enhancing knowledge sharing experiences. As practitioners, knowledge brokers have the capacity to link or bridge “knowledge-islands” and nurture dialogues between “….two or more employees and make transfer of knowledge possible” (Aalbers, Dolfsma and Koppius, 2004, p. 10). In the process of bridging knowledge producers with (re)users, we can generate new or reconstituted knowledge described as “brokered knowledge” (Meyer, 2010, p. 118). Brokered knowledge is co-created and reconstituted through human dialogues and knowledge sharing exchanges that use both social and technological tools. Through practice interventions as link agents, knowledge managers and capacity builders (Long, Cunningham and Braithwaite, 2013), knowledge brokers are able to contribute to the viability and effectiveness of networks, communicative interactions and knowledge sharing processes. Below is an illustration of how knowledge brokering as a practice intervention was realised in Charnwood Connect:

| As a Knowledge Management Officer for Charnwood Connect, my primary responsibilities were to develop and maintain an IT Knowledge Hub and a face-to-face practitioners’ forum as well as contribute to other project objectives. My role involved:

· Brokering inter-agency and inter-professional relationships

· Developing and facilitating online and face-to-face knowledge sharing platforms

· Nurturing a sense of common purpose and collective identity through collaborative work

· Co-creating artefacts such as an IT Knowledge Hub

· Developing shared practices such as a common referral system for clients.

|

Insights and possibilities

What we are able to report from this research which should be of interest to knowledge management practitioners is, that knowledge brokering can nurture knowledge sharing not just through technological solutions but also social processes and collaborative working. Such an orientation involves improving and increasing opportunities for face-to-face knowledge sharing, and making a more assertive business case for strengthening inter-professional relationships, co-creativity and collaborative enterprises. Niche knowledge brokers can be appointed to facilitate knowledge brokering experiences and help strengthen the capacity of other personnel such as line managers, supervisors and HR officers who have a latent responsibility for facilitating knowledge sharing. Niche knowledge brokers can work as co-practitioners with incidental knowledge brokers to create opportunities for knowledge sharing, make practice interventions and co-create, resulting in a net increase in the intellectual and social capital in organisations. Research (Ragsdell, 2009; Akhavan and Zahedi, 2014) has shown already that effective knowledge sharing is possible through events, senior managerial support, corporate strategies, staff development and nurturing knowledge sharing communities, yet we seem to have tilted the balance in favour of seeking more and more impersonalised managerial and technological solutions.

A further consideration that should be of interest to knowledge management academics, strategists and practitioners is the impact of social and organisational values on knowledge sharing behaviours, especially in organisations that provide person-centred services. Practice interventions and knowledge sharing encounters start from declared, implicit or subliminal social value positions and involve the “….unfolding and articulation of personal agendas, relations, influence strategies and knowledge transfer and diffusion over time” (Haas, 2015, p. 1040). It is through everyday professional practices, across-the-desk conversations, informal workplace encounters and after-work interactions that individual and collective values and beliefs manifest themselves, are endorsed or questioned. Human agency, values and beliefs are inseparable from knowledge sharing behaviours and preferences and knowledge brokering strategies have to take account of these, even where more impersonalised technological knowledge management solutions are deployed.

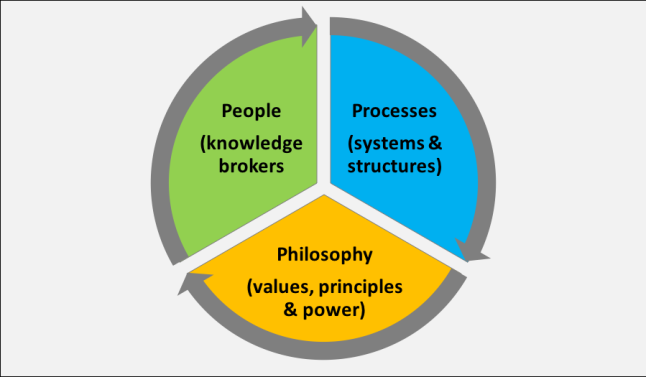

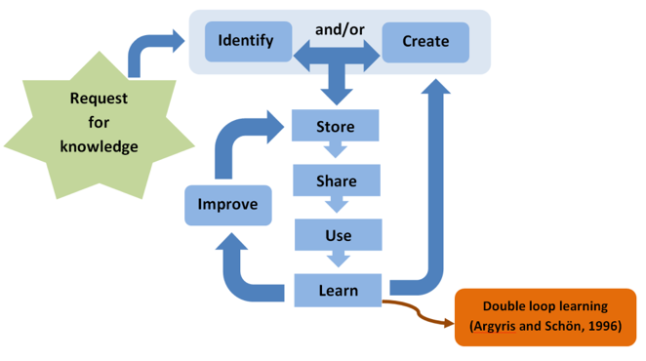

The research findings suggest that the fusion of three intertwined components are key to developing an effective knowledge brokering strategy in an organisation: people (knowledge brokers), processes (systems and structures) and philosophy (values, principles and power) (Figure 2). In this analysis, knowledge brokering extends beyond the impersonal mobilisation of knowledge, and instead involves facilitating in- and out-group relationships, in-person and virtual knowledge sharing dialogues and joint actions. The approach requires a more explicit acknowledgement of the power of human agency, the capability of individuals and groups to act in their social environments, and the knowledge broker as one in a constellation of knowledge practitioners and co-creators (Gherardi and Nicolini, 2002).

Figure 2: Knowledge brokering: An integrated approach

Conclusion

It is not always easy to actualise knowledge sharing in organisations, despite good intentions and policy declarations. Human agency in the persona of knowledge brokers who are integrated into routine work practices can act as complementary levers for knowledge sharing, collaborative working and joint action. Effective knowledge brokers and knowledge brokering processes can have a compound effect on realising knowledge sharing, build organisational capacity and improve services and, at the same time, validate and improve professional practices, status and standards.

References

Aalbers, H.L. & Dolfsma, W., 2015. Bridging firm-internal boundaries for innovation: directed communication orientation and brokering roles. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 36, pp.97–115.

Akhavan, P. & Zahedi, M., 2014. Critical success factors in knowledge management among project-based organisations: a multi-case analysis. IUP Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(1), pp.20–38.

Argyris, C. and Schön, D. A., 1996. Organisational learning II: theory, method, and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Inc.

Chauhan, V., 2018. Knowledge brokering: an insider action research study in the not-for-profit sector. PhD thesis. Loughborough: School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/handle/2134/35556

Cox, A.M., 2012. An exploration of the practice approach and its place in information science. Journal of Information Science, 38(2), pp.176–188.

Dalkir, K., 2005. Knowledge management in theory and practice.London: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Dixon, N.M., 2000. Common knowledge: how companies thrive by sharing what they know.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Evans, M., Dalkir, K. & Bidian, C., 2014. A holistic view of the knowledge life cycle: the knowledge management cycle (KMC) model. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(2), pp.148–160.

Gherardi, S. & Nicolini, D., 2002. Learning in a constellation of interconnected practices: canon or dissonance? Journal of Management Studies, 39(4), pp.419–436.

Greenhalgh, T. & Wieringa, S., 2011. Is it time to drop the “knowledge translation” metaphor? a critical literature review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104(12), pp.501–9.

Haas, A., 2015. Crowding at the frontier: boundary spanners, gatekeepers and knowledge brokers. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(5), pp.1029–1047.

Hendriks, P.H.J., 1999. Why share knowledge ? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge sharing. Knowledge and Process Management, 6(2), pp.91–100.

Hoult, M., Ragsdell, G., Davey, P. & Snape, P. (2018) Charnwood Connect: a holistic knowledge management strategy for the voluntary sector. K&iM Refer, 34(2), pp.19-22.

Long, J.C., Cunningham, F.C. & Braithwaite, J., 2013. Bridges, brokers and boundary spanners in collaborative networks: a systematic review. BMC health services research, 13(158), pp.1–13.

Markus, L.M., 2001. Toward a theory of knowledge reuse: types of knowledge reuse situations and factors in reuse success. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18 (1), pp.57-93.

Meyer, M., 2010. The rise of the knowledge broker. Science Communication, 32(1), pp.118–127.

Ragsdell, G., 2009. Inhibitors and enhancers to knowledge sharing: lessons from the voluntary sector. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice,10 (1), 1-10.

Schatzki, T.R., 2012. A primer on practices: theory and research. In Higgs, J., Barnett, R., Billett, S., Hutchings, M. & Trede, F., eds. Practice-based education: Perspectives and strategies. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. pp.13–26.

Serenko, A., Bontis, N., Booker, L., Sadeddin, K. & Hardle, T., 2010. A scientometric analysis of knowledge management and intellectual capital academic literature (1994‐2008). Journal of Knowledge Management, 14 (1), pp.3–23.

Teng, J.T.C. & Song, S., 2011. An exploratory examination of knowledge-sharing behaviours: solicited and voluntary. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(1), pp.104–117.

Ward, V., House, A. & Hamer, S., 2009. Knowledge brokering: the missing link in the evidence to action chain? Evidence and Policy, 5(3), pp.267–279.

Wenger, E., 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wiig, K.M., 1997. Knowledge management: where did it come from and where will it go? Expert Systems with Applications, 13(1), pp.1–14.

[1]Previously employed as a Knowledge Management Officer at Charnwood Connect, the basis of his doctoral research on knowledge brokering funded by the School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University, lotusconsultancyuk@gmail.com.

[2]School of Business and Economics, Loughborough University G.Ragsdell@lboro.ac.uk.

[3]Hoult, M., Ragsdell, G., Davey, P. & Snape, P. (2018) Charnwood Connect: A holistic knowledge management strategy for the voluntary sector. k&im REFER, 34(2), pp.19-22.

K&IM Refer 35(1), Winter 2019