Journal of CILIP’s Knowledge and Information Management Group Vol 33 (1) Spring 2017

Table of Contents

Welcome to the Knowledge & Information Management Group – ISG transformation

David Smith, Chair, K&IM National Committee

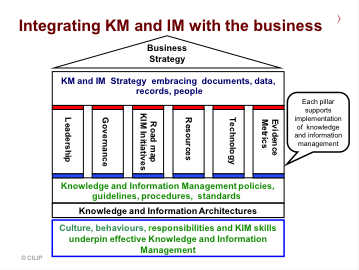

Information Management / Knowledge Management –

Two Sides of a Coin

Sandra Ward, Beaworthy Consulting

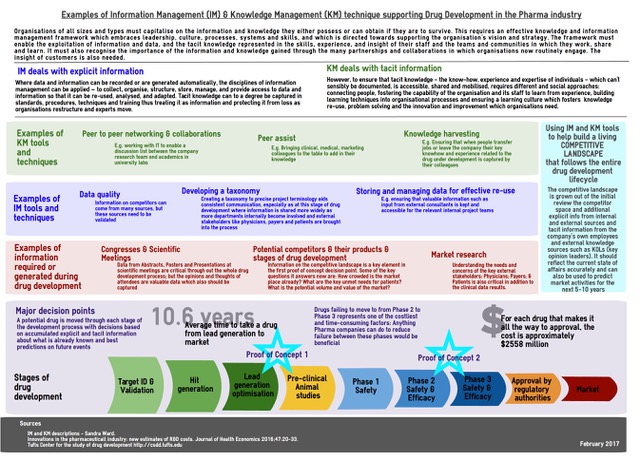

How Do Well-Implemented Information Management and Knowledge Management Programmes Assist the Drug Development Process in the Pharma Industry?

Denise Carter, DCision Consult

Passing a Verdict: Knowledge Management in a Top Law Firm

Jonathan Cowley

Finding Out What Our Researchers Really Want:

The Structured Interview

Mary Betts-Gray, Cranfield University

Opportunities in Research Data Support: The Data Librarian’s Handbook

Helen Edwards, Editor, Refer

Review: British Librarianship and Information Work 2011-2015

Lynsey Blandford, Canterbury Christ Church University

Announcements

CILIP Knowledge and Information Management Briefings

Recruiting and Developing Knowledge and Information Professionals

14 June 2017 at CILIP HQ

https://www.cilip.org.uk/recruitingki

Cybersecurity for Knowledge and Information Professionals

19 October 2017 at CILIP HQ

https://www.cilip.org.uk/cybersecurity

Knowledge and Information Management Group

Information Resources Awards 2017

Have you spotted a notable information resource recently?

If you did, why not nominate it for the Knowledge and Information Management Group Information Resources Awards 2017

We are looking for outstanding information resources, whether in print or electronic format, that are available and relevant to the knowledge, information management, library and information sector in the UK.

Print nominations must have been published between 1st January and 31st December 2016, and electronic nominations must be currently available and accessible.

Closing date for nominations is 30th June 2017

Submit your nominations at: https://goo.gl/forms/e3NOIPYoeV09W7y03

Knowledge and Information Management Walford Award

Do you know someone who has made an outstanding contribution to knowledge and information services in the UK?

If you do, why not nominate them for the Knowledge and Information Management Walford Award 2017

Nominations are welcome from anyone who knows and respects the work of the nominee.

Nominations close on 31st July 2017

Submit your nominations at:

https://goo.gl/forms/ku8j1HzwtZHMIKxE3

K & IM Refer: the journal of the Knowledge and Information Management Group of the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP), is published three times a year and distributed free to members of the Group.

Editor: Helen Edwards

Editorial team: Lynsey Blandford, Ruth Hayes

Cover Design: Denise Carter

Contact: Helen Edwards 07989 565739; hogedwards@gmail.com

Copyright © The contributors and the K & IM SIG 2017

Online edition https://referisg.wordpress.com

ISSN: 0144-2384