Joy Caisley, Julian Ball, Matthew Phillips. University of Southampton Library

Introduction

The Library at the University of Southampton has a particularly strong collection of printed British Official Publications, known as the Ford Collection. The collection is named after the late Professor Percy Ford and his wife Dr Grace Ford who brought the collection to the University of Southampton in the 1950s from the Carlton Club and conducted research based on the collection. Hoping to “increase both the appreciation and the use of…”official publications, Ford (1951, p. vii), the Fords compiled ‘breviates’ or ‘select lists’, in seven volumes covering the years 1833 – 1983. These were not catalogues of all British Official Publications. Instead the Fords identified and summarised documents which “have been, or might have been, the subject of legislation or have dealt with ‘public policy’ ”, Ford (1951, p. ix).

The work of the Fords was the impetus behind our later activities when, in 1995, we began using a database rather than a card-file to catalogue and abstract new additions to the Ford Collection. Initially this was on a stand-alone computer for our own internal use, but later offered as an internet service, BOPCAS (British Official Publications Current Awareness Service), which some of you will remember. As technology moved on and external funding opportunities arose, we extended our indexing to cover older publications and moved into full-text digitisation, so making many publications freely available to all. Although funding sources were for specific tasks and periods, the Library continues to work unfunded with these valuable digital collections in 2016 to ensure that they are made fully accessible for readers worldwide. The notes which follow are primarily about ‘what happened next’ with regard to BOPCRIS and EPPI, two of a cluster of official publications digitisation projects with which we were concurrently involved from 2001 to 2007.

Historic Background

BOPCRIS and EPPI were projects funded by NOF and AHRC, which aimed to make British Official Publications more ‘findable’, available online and all free of charge to the user.

BOPCRIS: British Official Publications Collaborative Reader Information Service. This project aimed to index and abstract a selection of 18th – 20th century official publications, primarily Parliamentary but also with some non-Parliamentary. The documents chosen for inclusion were mainly those selected by the Fords. Information about locations of printed copies was to be provided and it was planned to provide digital copies of a selection. The best description still available online can be seen here, from our then technical partners at Bristol University’s ILRT division: http://www.bris.ac.uk/ilrt/people/project/713

However, time, money, storage costs and no exit strategy meant that the University of Southampton had to abandon some of our aims (w.e.f. 1st August 2009). We moved the bibliographic records to our online catalogue, WebCat (http://www-lib.soton.ac.uk/, which ensures that the records can be found via COPAC, but the abstracts could not be imported. The digitised versions of those selected were stored, in the hope that they would in future find a home. Sadly, not all of those scans survived, but some did.

EPPI: Enhanced Parliamentary Papers on Ireland, 1801 – 1922. This project began with the explicit mission to not only catalogue, but also to provide digitised versions of about 14,000 British Parliamentary papers on Ireland. The EPPI website proved of great interest to family historians as a full-text search could be conducted across the whole set. Its demise led to many cries of anguish from that quarter!

As with BOPCRIS, in August 2009 we moved EPPI’s bibliographic records to our online catalogue, WebCat. The scans were archived, but we also passed the digital files to ‘DIPPAM – Documenting Ireland: Parliament, People and Migration’ (http://www.dippam.ac.uk/) whilst retaining our right to further publish them given the right circumstances.

The scanned EPPI documents were later made freely available via links from the WebCat records. The images were stored on our internal servers and storage costs continued to be an issue. Apart from the storage costs, linking to PDFs via WebCat is rather clumsy as long papers had to be split down into small files to achieve a reasonable download time.

18th Century Parliamentary Publications (1688-1834). With JISC funding we digitised and presented over one million pages of printed parliamentary texts sourced from the University of Cambridge, British Library and the University of Southampton. Without any post-project funding and a requirement to curb our annual storage fees for 15TB of data we entered into a time-limited exclusive agreement with Chadwyck-Healey/ProQuest and they added the 18th century materials to HCPP (House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online, now known as U. K. Parliamentary Papers). This material remains free to the UK Higher Education community via that ProQuest service.

What’s happening now?

Partly through pragmatism (storage and maintenance costs), but also some idealism (the greater good of the wider research community), we have started moving the existing digitised items to the Internet Archive. Two sub collections have been established under the ‘Library Digitisation Unit, University of Southampton’ in Internet Archive (IA) called ‘British Parliamentary Publications’

(https://archive.org/details/britishparliamentarypublications) and ‘British non-Parliamentary Publications’

(https://archive.org/details/bopcris). These sub collections hold all the previously digitised EPPI papers, BOPCRIS papers and the non-Parliamentary Publications that are being currently digitised by the in-house Hartley Library Digitisation Unit (LDU). These and other resources from the University of Southampton can be found at:

https://archive.org/details/universityofsouthamptonlibrary

In total there are 14,270 digitised papers in the ‘Parliamentary Publications’ collection on IA. The non-Parliamentary set is still growing, but currently comprises about 1,850 documents selected for BOPCRIS, most dating from the 1950s through to the mid-1980s. We are particularly proud of the non-HMSO/TSO documents, e.g. https://archive.org/details/op1275609-1001 , Trespass on residential premises, a 1983 Home Office consultation, 26 pages, typed, published by the Home Office itself.

We are also working on digitising some early 20th century publications relating to transport in order to support a specific current strand of research at the University of Southampton,

e.g. https://archive.org/details/railways00566422 . We hope to continue steadily digitising from our own collections of non-Parliamentary publications, irrespective of subject matter.

Internet Archive was chosen for the delivery of the materials from the Hartley Library as:

- It has a large corpus of materials that readers worldwide know about and can easily access

- Materials added from our collection join similar subject resources made available by other institutions thus building towards an extensive collection

- It provides a sustainable delivery mechanism for resources

- Materials are also made available from other portals that download or link to data in Internet Archive

- IA provides an archive of master imagery that can be retrieved by the depositing institution

- The printed texts are optically character read (OCR) by IA using the Abbyy software

- IA provides a free delivery service for institutions wishing to provide free open access to their digital collections however large or small

Licensing

We provide the resources online under the Open Government Licence and the metadata of each publication carries the text, “Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.” A Creative Commons licence is also associated with the metadata for each publication with Usage Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Can you help?

If you see errors (e.g. missing pages or poor scans) please let us know. If you spot that we have digitised most of a series but are missing bits you have, do get in contact!

We know that our efforts regarding the non-Parliamentary publications cannot be comprehensive. Our original collection was formed by the Fords, who ‘rescued’ many items as well as collecting in their own areas of interest. There is no definitive catalogue against which we can check departmental publishing. We know that we are privileged to have this collection, even with its gaps, so our aim is simply to broaden access to the extent we can.

We will always welcome any approaches regarding collaborative bids to digitise even more content.

References and acknowledgement

The portrait of the Fords was painted by Juliet Pannett, © 1974, and is reproduced by the kind permission of her son, Denis Pannett.

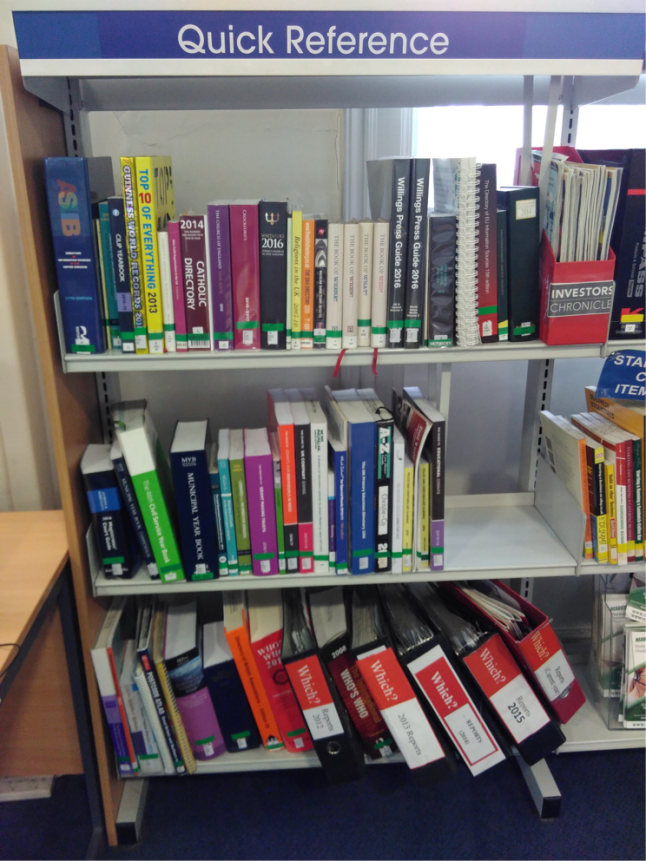

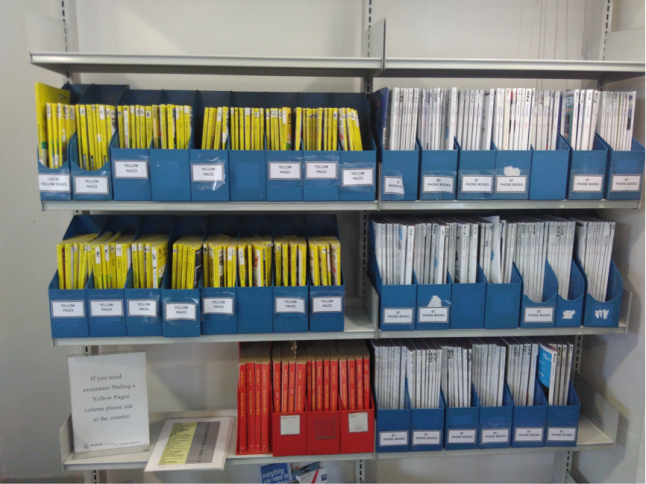

Other images are from: Great Britain. Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (1959) What they read and why: the use of technical literature in the electrical and electronics industries. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. (Problems of Progress in Industry -4) [Online]. Available at

https://archive.org/details/op1266910-1001.

Ford, P. and Ford, G. (1951) A breviate of Parliamentary papers 1917-1939. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

All web pages accessed and addresses correct, May 16th 2016.

Refer 32(2) Summer 2016